[column width=”1/1″ last=”true” title=”” title_type=”single” animation=”none” implicit=”true”]

DECLARATION OF THE KITSUMKALUM INDIAN BAND OF THE TSIMSHIAN NATION OF ABORIGINAL TITLE AND RIGHTS TO PRINCE RUPERT HARBOUR AND SURROUNDING COASTAL AREAS

KITSUMKALUM INDIAN BAND OF THE TSIMSHIAN NATION OF ABORIGINAL TITLE AND RIGHTS TO PRINCE RUPERT HARBOUR AND SURROUNDING COASTAL AREAS

- Introduction

This declaration is made by the Elected and Hereditary Chiefs of Kitsumkalum on behalf of all Kitsumkalum.

Kitsumkalum is a strong, proud part of the Tsimshian Nation. We take exception to attempts to deny us our rightful place within the Tsimshian Nation and to deny us our rightful place on the coast, with its sites and resources that are an integral part of who we are.

This denial is more than an attempt to separate us from our lands and resources, it is an assault on who we are as people. We are supposed to be moving forward with Canada and British Columbia in a spirit of recognition and reconciliation. Instead, we are met with denial and resistance.

In this declaration, we once again assert who we are and what is ours. We are a part of the Tsimshian Nation that exclusively occupied the Prince Rupert Harbour and surrounding coastal and inland areas as of 1846. Within that area, we hold exclusive ownership over and responsibility for specific sites in accordance with ayaawx, Tsimshian Law. We have aboriginal rights to fish, harvest, gather and engage in cultural and spiritual activities throughout the coastal part of our territory.

There is much at stake – in particular with a Liquefied Natural Gas (“LNG”) industry at our doorstep. It is only through recognition on the part of Canada and British Columbia of our rights and title and an acknowledgment of your legal obligations to consult meaningfully with us that we can move forward in a spirit of mutual respect and work to achieve results for our mutual benefit.

[/column]

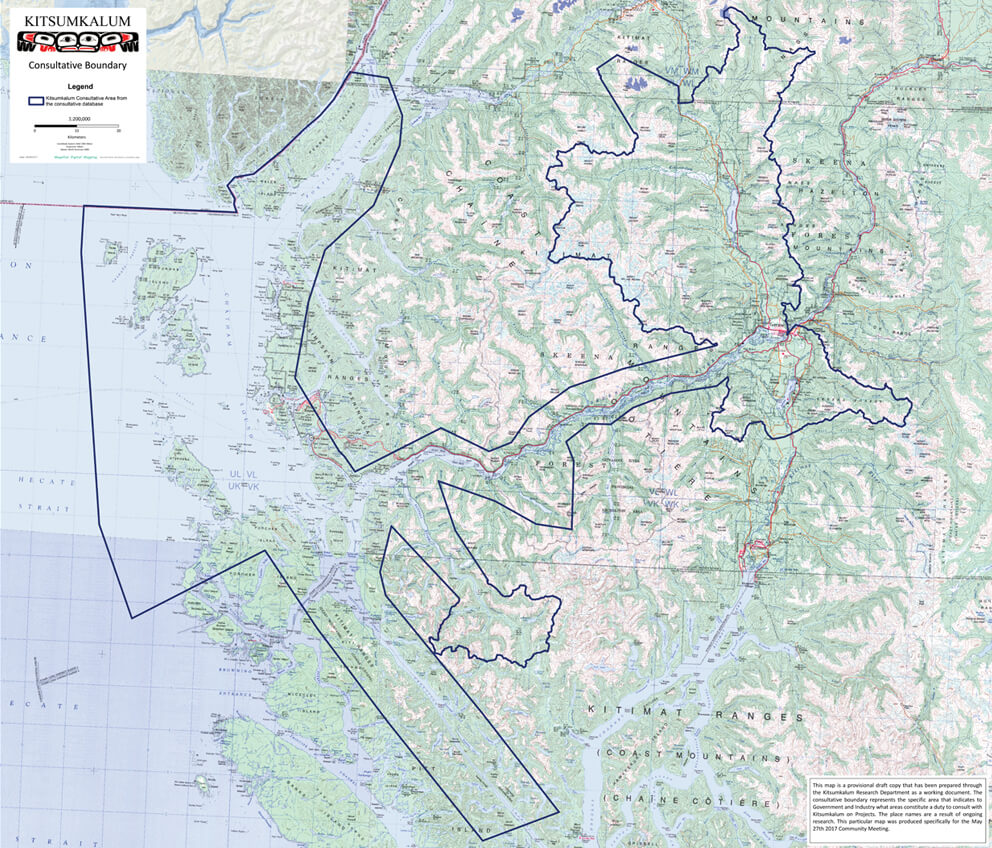

[column width=”1/1″ last=”true” title=”Kitsumkalum, a Tsimshian Tribe – Consultative Area Map – Our Laxyuup” title_type=”single” implicit=”true”]

[iframe src=”https://www.google.com/maps/d/embed?mid=1tFErLEf7OSXuOuUANlx33ztNohc” width=”100%” height=”700px”]

[/iframe]

[/column]

[column width=”1/1″ last=”true” title=”” title_type=”single” animation=”none” implicit=”true”]

- Background

In a letter from Transport Canada dated August 28, 2012, the federal government advised that it has assessed Kitsumkalum’s claim of Aboriginal title and rights within the Prince Rupert Harbour area to be “very weak”. In this letter, Transport Canada asserted:

There is little, if any, direct evidence that these groups traveled to or used and occupied the Prince Rupert Harbour area at the date of contact (1793), or until the late 19th century. There is some evidence that Kitsumkalum traveled to trade at Fort Simpson in about 1840, but little if any direct evidence to support a claim of Aboriginal rights to Kaien Island or Ridley Island. There is no evidence to support a claim to Aboriginal title.

In reaching this conclusion, Transport Canada stated that Canada’s assessment “relies heavily” on a report prepared for Canada by Joan Lovisek, entitled Prince Rupert – Port Fairview: Aboriginal Occupation of Prince Rupert Harbour Area dated August 20, 2009 (revised in 2010) (the “Lovisek Report”).

Kitsumkalum responded to the August 28 letter on September 14, 2012, expressing our strong disagreement with this assessment and inquiring as to how Canada specifically used the report to determine the assessment. Canada effectively ignored this request by simply noting that Kitsumkalum had a copy of the Lovisek Report.

This assessment has formed the basis for Canada and British Columbia’s approach to consultation with Kitsumkalum – one that will significantly hamper our meaningful participation in dialogue with respect to the proposed development of the LNG industry in Kitsumkalum Territory.

The purpose of this declaration is to demonstrate that the assessment is incorrect. This declaration describes:

- the significant inconsistencies and gaps in the Lovisek Report that demonstrate its unreliability as a basis for an assessment of the strength of our claim of Aboriginal title and rights;

- how Kitsumkalum was and is an integral part of the Tsimshian Nation that exclusively occupied the Prince Rupert Harbour and surrounding coast at the time of first contact with Europeans and as of 1846;

- how Kitsumkalum, as part of the Tsimshian collective, and in accordance with Tsimshian law, asserts ownership to specific sites in the Prince Rupert Harbour and surrounding coast;

- Kitsumkalum’s strong connection to the Prince Rupert Harbour and surrounding coast through our historic and current occupation and use of the Prince Rupert Harbour and surrounding coast, including through the exercise of our aboriginal rights that has been integral to our culture since before first contact with Europeans.

Please note that this declaration is not intended to be a comprehensive report. We are continuing to compile information that substantiates for the government what our elders have taught us and what we know as Kitsumkalum – that the coast is part of who we are and that our title and rights in that area must be recognized and protected.[1]

III. Critique of Lovisek Report

Given that Canada has incorrectly relied on the Lovisek Report to reach the conclusion Kitsumkalum has a “very weak” strength of claim to the Prince Rupert Harbour and surrounding coast, it is a necessary starting point to identify the numerous and severely inaccurate statements made throughout the Lovisek Report, as well as the gaps in the analysis.

The main basis of Dr. Lovisek’s erroneous conclusions is her use of the term “Coast Tsimshian” as being a separate group, comprising of Lax Kw’alaams and Metlakatla, from the larger Tsimshian Nation. Dr. Lovisek relies on, and misuses, secondary sources to lend support to this artificial category. By so doing, her report is plagued by inconsistency. While Dr. Lovisek acknowledges the many gaps and lack of evidence with respect to the ownership of the Prince Rupert Harbour area, she draws conclusions that the area was occupied by the “Coast Tsimshian”, without providing adequate evidence in support. In addition, she includes factual inaccuracies with respect to Kitsumkalum, and disregards evidence which supports Kitsumkalum as a Tsimshian Nation with aboriginal title and rights to the Prince Rupert Harbour and surrounding coast. This is most likely due to her failure to canvas and review the complete record of ethnographic and historical materials concerning Kitsumkalum.

- Fabrication of the term “Coast Tsimshian”

There are numerous instances throughout her report where Dr. Lovisek relies on, and misuses, secondary sources to put forward the idea that there was or is a “Coast Tsimshian”. Dr. Lovisek herself points out that the secondary materials are equivocal in terms of their support for her conclusions. For instance, she notes Wilson Duff’s extensive review of Marius Barbeau’s and William Beynon’s collection of work on Tsimshian. With respect to a map that she relies upon for the formulation of the “Coast Tsimshian” theory, she recognizes Duff’s caution that the maps “are not of the degree of precisions one would desire” and “imply a degree of accuracy which the data do not support”.[2] In other instances, Dr. Lovisek fails to recognize, or at least acknowledge, this fundamental problem. For example, while relying to a great extent on Viola Garfield, she fails to acknowledge Garfield’s own admission that there was a lack of “historical depth” in her data.[3]

Dr. Lovisek states that “anthropologists distinguish three separate groupings of Tsimshian known as the Coast Tsimshian, Canyon Tsimshian and Southern Tsimshian”.[4] To support this statement she cites a map from the Handbook of North American Indians, volume 7, The Northwest Coast.[5] However, this map is labelled as the “linguistic division of the groups” – it is not in any way based on geographical use or occupation. Further, it is inaccurate. There is no linguistic division between Kitsumkalum and Lax Kw’alaams and Metlakatla, the so-called Coast Tsimshian. Dr. Lovisek herself acknowledges that there is no such division. When describing Kitsumkalum as a “Canyon Tsimshian”, she states that they “speak the same dialect as the Coast Tsimshian”.[6] But Dr. Lovisek does not attempt to reconcile these contradictory statements. Instead, she misuses and contradicts the reference to lend support to her theory that there is a “Coast Tsimshian”.

The reason that we speak the same dialect as the “Coast Tsimshian” is that there is no such thing as “Canyon Tsimshian” and “Coast Tsimshian”. While attempting to support a distinction between groups, Dr. Lovisek relies upon a reference that incorrectly asserts that the Tsimshian is divided based on dialect, and proceeds to state in her report there is no such distinction.

Importantly, while the Lovisek Report has been relied upon by Canada to distance Kitsumkalum from the coast, Dr. Lovisek actually draws an opposite conclusion with respect to specific areas that feature a Kitsumkalum interest in the Prince Rupert Harbour area. She writes:

Duff stated that based on information obtained from an informant named Wallace in 1926, that Kennedy Island, Smith Island and De Horsey Island: “were the common property of all the Tsimshian tribes,” as presumably was the coastal area in the vicinity of Metlakatla farther north.[7]

This quote is notable for the fact that it is entirely contradictory to her central thesis and rather supports Kitsumkalum’s understanding of the common interest that the Tsimshian hold in areas on the coast.

Furthermore, Dr. Lovisek relies upon William Beynon’s description of these islands as “common property for the Coast [sic] Tsimshian”.[8] However, Beynon’s work is problematic. He arrived late into Tsimshian culture, did not collect information directly from Kitsumkalum and relied upon information collected by others, most notably Marius Barbeau. Barbeau himself characterized Beynon as “not well versed in Indian matters”[9] Beynon’s overall characterization of “Coast Tsimshian” must therefore be approached with caution, in particular given his own acknowledgement of Kitsumkalum’s coastal sites elsewhere in his writings and given the general lack of substance or basis for this thesis.

Further, Dr. Lovisek points out that Duff (following Wallace), refers to the named islands (Kennedy, Smith and DeHorsey) as “the common property of all the Tsimshian tribes”.[10] However, elsewhere she refers to those same islands as an example of “…common property for members of the same local group, (i.e. all Coast Tsimshian)…”[11]

This is one of several examples of Dr. Lovisek making contradictory statements, usually on account of misusing secondary sources to support an argument that has no foundation based upon the primary data.

In our view, Dr. Lovisek adds the “coastal” distinction because it supports her false conclusion with respect to the vacuum she alleges existed further north in the Prince Rupert Harbour area. But that distinction is, as just pointed out, wholly unsupported by the evidence: Duff and Wallace refer to the islands as “the common property of all the Tsimshian tribes”, drawing no distinction as to their “coastal”, “southern”, or “canyon” origin. Indeed, it may be for that very reason that Dr. Lovisek does not even cite either Duff or Wallace on page 7 of her report.

There is no “Coast Tsimshian”. It is a term that Dr. Lovisek relies on, with no basis, to provide artificial support to her inaccurate conclusions.

- Gaps/Lack of Evidence

Dr. Lovisek’s report is plagued with uncertainties and lack of evidence, which in some cases she readily admits. Unfortunately, despite this, she proceeds to draw conclusions that have no factual or evidentiary basis.

For instance, Dr. Lovisek states there is “no information in the ethnographic or historical records that dates to approximately 1846 about any group having exclusive use and ownership of the land and resources in the Prince Rupert Harbour area, specifically Kaien Island and Ridley Island.”[12]

In our view, this lack of evidence of “Coast Tsimshian’s” exclusive ownership of the Prince Rupert Harbour area supports Kitsumkalum’s claim that these were Tsimshian areas used by all Tsimshian people. The reason there was no information identifying exclusive use and ownership by “any group” is because it was all held by Tsimshian, and because of that, it is impossible to attribute the Prince Rupert Harbour area to just a portion of the Tsimshian.

Further, Dr. Lovisek fails to take into account that within the Tsimshian collective, there existed specific ownership of settlement sites and the associated beachfront. This specific ownership is not contradictory to common ownership of the gathering area in Tsimshian law. Dr. Lovisek thus demonstrates both her lack of knowledge and understanding of the Tsimshian law of land use and ownership, and makes it clear that Kitsumkalum’s place within the Tsimshian was not a focus of her report. She is dismissive of Kitsumkalum’s aboriginal title and rights claims to the coastal areas without having made sufficient inquiries or conducted adequate research.

Other examples of her admission of the lack of evidence include:

- “Although the archaeological evidence suggests that Kaien Island and Ridley Island were used by aboriginal people for forest utilization in the form of CMTs, the identity of the aboriginal peoples and the dates of the CMTs have not been determined.”[13]

- there is “no evidence in the ethnographic or historical literature that Kaien Island or Ridley Island was an area of joint exclusive use by one or more of the Lax Kw’alaams and Metlakatla, Gitxaala, Kitselas and Kitsumkalum.”[14]

There are several other similar admissions throughout her report. Given these gaps in evidence, the inaccurate use of the term Coast Tsimshian, and the lack of understanding of Tsimshian land use and ownership, Dr. Lovisek draws erroneous conclusions that paint the inaccurate picture that Kitsumkalum is not Tsimshian proper and did not use and occupy the Prince Rupert Harbour area and surrounding coastal sites.

- Factual Inaccuracies concerning Kitsumkalum

Dr. Lovisek puts little effort into describing Kitsumkalum, which is not surprising given that Kitsumkalum was not the focus of her report. However, she does do an injustice to Kitsumkalum by: asserting inaccurate statements, disregarding evidence that supports Kitsumkalum as a Tsimshian tribe on the coast, and failing to do a comprehensive review of the historical records.

Dr. Lovisek asserts that Kitsumkalum’s seasonal round was confined to the canyon area of the upper Skeena River and that we started to visit the post at Fort Simpson in about 1838.[15] It has been well documented that Kitsumkalum was not so confined. Unfortunately, Dr. Lovisek did not consult or review the complete record of publications relating to Kitsumkalum. If she had, she would have read about Kitsumkalum’s use of coastal and river areas in Men of Medeek.[16] She also fails to research what was an obvious flaw in her logic – if Kitsumkalum was so confined to the canyon, how did we have ocean capable canoes in order to reach Fort Simpson? How would we have known how to travel to reach that Hudson’s Bay post? Our use of the coast was, in fact, never so confined.

Further, Dr. Lovisek states that the emergence of the canneries in the 1870s at Port Essington contributed to a migration of Kitsumkalum and Kitselas from the canyon south to the coast.[17] She notes a private reserve was established and occupied by the two Indian bands at Port Essington. Our oral histories, however, indicate that Kitsumkalum was at Port Essington long before the canneries.

For example, Charles Nelson, the Ganhada Sm’oogyet of Kitsumkalum who had the title Xpilaxha, addressed the Royal Commission of Indian Affairs at Port Essington in 1915. He stated “…it is not a new place – it is a place that was handed down from one generation to another…”[18] That we were long time occupants of Port Essington was confirmed by an Indian Reserve created for Kitsumkalum and Kitselas (both “inland” Bands if Dr. Lovisek is to be believed).

Inaccuracies about our connection to Port Essington are, like the artificial creation of a distinction between Tsimshian, contrary to the historical record.

- Inadequate Review of Historical and Ethnographic Records

Dr. Lovisek’s report is incomplete with respect to Kitsumkalum, specifically with respect to Kitsumkalum’s title and rights in areas beyond the Skeena and the mouth of the river. We have identified numerous sources which Dr. Lovisek (as well as Canada and British Columbia) ought to have reviewed in order to present an accurate and complete account of Kitsumkalum’s use and occupation of the Prince Rupert Harbour area and surrounding coast, and our place within the Tsimshian Nation. Dr. Lovisek’s failure to conduct a comprehensive review of all available sources renders her report incomplete and unreliable.

This failure to review all information is highlighted by Dr. Lovisek’s acknowledgement that “…Skeena River groups…began to gradually take up camp sites on the coast.”[19] Despite this, Dr. Lovisek fails to review the extensive material that might corroborate our presence in precisely the coastal locations where our oral traditions place us. For example, Dr. Lovisek:

- fails to canvas at all some of the ethnographic material that pertains specifically to the Kitsumkalum (eg, Men of Medeek, Boas circa 1880s);

- fails to canvas some of the ethnographies of other specific Tsimshian First Nations that might, upon inspection, indicate the presence of still other First Nations, including the Kitsumkalum, in the Prince Rupert Harbour and other areas (eg. Menzies at Kitkatla, Jendzowsky at Kitselas);

- fails to canvas at all some of the ethnographic material that pertains to the Tsimshian generally, and which may contain information that pertains specifically to the Kitsumkalum and its title and rights in the Prince Rupert Harbour (eg, Dorsey, Homer Barnett field notes);

- With respect to archival information, fails to canvas potentially valuable sources including but not limited to DIA BC Region and Nass Agency records, trapline applications, hand logging applications, missionary correspondence and newsletters, and fishing data; and

- fails to go beyond HBC Fort Simpson post journals (and even with that source her conclusions are vague and tentative due to her obviously incomplete review of the material), and ignores other potentially valuable sources of HBC information that might include Kitsumkalum references. These sources would include ship logs and journals (eg., Beaver, Dryad and other ships), other post records (eg, Port Essington 1835 (if such records exists)), and higher level reports and correspondence from the HBC district and regional level to London (eg., originating in Fort Vancouver and Fort Victoria).

A review of these sources is an essential element of any assessment of Kitsumkalum’s interests on the coast. So too would be actual dialogue with Kitsumkalum, which Dr. Lovisek also failed to do.

This is not surprising, in part because Kitsumkalum was not the subject of the Lovisek Report. It is worth noting the context in which this report was prepared:

I have primarily relied upon documents used or consulted in preparation of my report and review of expert reports regarding commercial rights to marine resources by the Lax Kw’alaams Indian Band and Others v. The Attorney General of Canada and Her Majesty the Queen in Right of the Province of British Columbia, February 2007.[20]

The Lovisek Report is an opinion that relies entirely on research conducted by, and reports prepared by, others. It was not subjected to any scholarly review for validity or reliability, such as peer review. Had the study been peer reviewed, Kitsumkalum’s perspectives about the incompleteness of the research and the inaccuracy some of the conclusions reached, would be confirmed.

Note that the British Columbia Supreme Court has cautioned against blindly accepting perspectives and hypotheses of consultants, including the Lovisek Report:

I have not ignored any of the expert reports of Drs. MacDonald, Anderson, Langdon and Lovisek but have availed myself of their conclusions only where I am satisfied they are truly supported by the specific evidence in this case, and not merely broad-based assertions pronounced in favour of the position of one or other of the litigants.[21]

In sum, the Lovisek Report erroneously asserts that the “Coast Tsimshian” is comprised of Lax Kw’alaams and in part Metlakatla and further states that at contact, Kitsumkalum was a distinct political identity which occupied and used land within ethnographically defined territories which did not include Prince Rupert Harbour.[22] Dr. Lovisek repeatedly relies on this “Coast Tsimshian” distinction, but does so without evidentiary basis. In fact, the preponderance of evidence (including evidence utilized in the Lovisek Report itself) suggests that there was no such distinction, and that the areas in question were occupied by the Tsimshian people as a whole.

We have listed several other sources which need to be considered in order to make a true assessment of Kitsumkalum’s strength of claim to the Prince Rupert Harbour and surrounding coast. A weakness of the early literature on the Tsimshian is a failure to include Kitsumkalum. Those that did include Kitsumkalum in the literature, including Boas and Barbeau, did so in only a cursory way.

Since the 1980’s, however, researchers involved with community-centred studies specifically about Kitsumkalum have published a significant amount of information. These have not been given sufficient attention in the modern literature, including in the Lovisek Report. A comprehensive review of the sources that have to this point been overlooked is necessary to address the false distinction within Tsimshian that informs British Columbia and Canada’s consultation approach with Kitsumkalum.

- Kitsumkalum as a Tsimshian Nation

Kitsumkalum has, since time immemorial, been an integral part of the Tsimshian Nation. The Tsimshian Nation exclusively occupied the Prince Rupert Harbour area and surrounding coast at the time of contact and as of 1846. Not only was Kitsumkalum essential to the collective that occupied the coast, but in accordance with Tsimshian law, ownership of certain sites and the responsibility for their care and control rests with Kitsumkalum. Kitsumkalum remains an important part of the Tsimshian Nation and continues to maintain a connection to the coast through our presence in the Prince Rupert Harbour area and surrounding coast, and our heavy reliance on the resources in the area.

As described above, relatively recent redrafting of Tsimshian geography creates a distinction between the Lax Kw’alaams and Metlakatla Indian Reserve communities as the “Coast Tsimshian”. Kitsumkalum does not dispute, and in fact fully endorses the fact that there were common territories on the coast that all Tsimshian could use. Use of these common grounds were not, however, limited to the so-called nine tribes, despite the claims made by the Lax Kw’alaams Indian Band when they submitted a map to the ICC in 1994, or the July 1999 map of the Allied Tsimshian Tribes. Rather, all the Skeena River tribes were integrated into the coastal communities of Port Simpson/Lax Kw’alaams, Metlakatla, and Port Essington through kinship, marriage, and residence. The historical record found in oral histories and written sources provide evidence of this integration. It should be noted that the Lax Kw’alaams were not successful in court when they asserted an aboriginal right to fish on the coast, largely because they were unable to establish exclusivity at the expense of the rest of the Tsimshian.

- Shared Genealogy with Lax Kw’alaams and Metlakatla

Kitsumkalum shares a common ancestry with Lax Kw’alaams and Metlakatla. We assert our common heritage with all Tsimshian, including those Tsimshian who, through the dictates of the Department of Indian Affairs, are now deemed to be members of the Lax Kw’alaams and Metlakatla Indian bands. However, it is important to note that at contact, there were no such groups as Lax Kw’alaams and Metlakatla. Instead, all Tsimshian tribes were interconnected through intermarriages, Houses and associated lineages.

As Dr. Lovisek herself wrote:

At contact there were no groups known as the Lax Kw’alaams and Metlakatla. At contact there were ten autonomous discrete named groups with distinct political identities known by their village names. After these ten named groups migrated to Fort Simpson in 1840 they retained their distinct names but formed a new collective identity and political organization and came to be known as the Lax Kw’alaams. In 1862, part of the Lax Kw’alaams and aboriginal peoples from other communities such as the Kitselas, Kitsumkalum and Gitxaala and others migrated from Fort Simpson to Metlakatla where under the auspices of William Duncan of the Church Missionary Society established a new community known as Metlakatla. In 1846, the Metlakatla did not exist as a distinct identity.[23]

Kitsumkalum has conducted research into the genealogy of our members and connections with other Tsimshian tribes. The current registered Kitsumkalum Band membership includes several lineages associated with the nine Galts’ap (or tribes) of Lax Kw’alaams and Metlakatla. Likewise, the current registry of Lax Kw’alaams and Metlakatla includes Kitsumkalum people, and has done so since the Department of Indian Affairs artificially created these divisions among the Tsimshian Nation. Since then there has been a population flux with people switching registration back and forth between the Indian bands created by Canada.

Centred as it now is at the Kitsumkalum Reserve, our community currently includes several lineages that are associated with the Galts’ap represented in the villages of Lax Kw’alaams, Metlakatla, and other reserves. An example is the important House of Waaps Niskiimas, the Ganhada group from the Giluts’aaw who hold territories in the Lakelse watershed. Despite the fact that the Giluts’aaw has a small population in Lax Kw’alaams, Lax Kw’alaams claims exclusive representation for all Giluts’aaw.

This is not the only example of lineages who consider themselves to be part of Kitsumkalum but who are part of the Galts’ap that Lax Kw’alaams claims as exclusively belonging to Lax Kw’alaams and Metlakatla. Some other examples include lineages associated with the Ginaxangiik, Gispaxlo’ots, the Gitzaxłaał, and the Gitwilgyoots.[24]

In speaking to Kitsumkalum’s connection to Kaien Island, Kitsumkalum Elder and matriarch, Ganhada Addie Turner explained the connections between all the Tsimshian Nations:

Probably all [Tsimshian, including Kalum]went down there [Casey Point area]. My grandfather was Kalum but he lived in Metlakatla… Peter Nelson. That was my Grandfather’s brother but we called him Grandpa he actually he was our great Uncle, but with our own standard [the Tsimshian culture]he’s Grandpa.

… I don’t know if they owed land but they it seems like they [did], they got along so good. Because it would [seem like we did own property there]…, we were both Metlakatla, Port Simpson and Kalum and ah, well I think, Kitselas was pretty close with us too. You know, but these three [communities] were really close. We would all use the same language. And, we shared the resources there.

Kitsumkalum has always been intimately connected to its other Tsimshian tribes through marriages, adoptions, and the sharing of resources in their common grounds. The distinction of Lax Kw’alaams and Metlakatla as “Coast Tsimshian” is a relatively recent fabrication that does not accurately reflect the people using and occupying the Prince Rupert Harbour and surrounding coast.

- Historically Tsimshian

Kitsumkalum has historically been known as “Tsimshian”. Kitsumkalum elders assert their common heritage with all Tsimshian and point out that the name Tsimshian translates as “in the Skeena”, a descriptive term that should include not only the nine tribes of Lax Kw’alaams and Metlakatla but also Kitsumkalum and Kitselas. Indeed, there is also plenty of archival and published evidence that the understanding of “Tsimshian” includes the community of Kitsumkalum.

The label “Coast Tsimshian” is a relatively recent fabrication. For example, in the reserve creation process, Indian Commissioner O’Reilly referred to Kitsumkalum in his minutes of decisions in 1891 as “Tsimpsean Tribe, Kitsum-kay-lum Indians”.[25] Likewise, in 1859, Paul Kane who “recorded a census of the Indian Tribes inhabiting the Northwest Coast of America for the year 1846” recorded “Kee-chum-a-kai-lo (Kitsumkalum) … Trade at Fort Simpson, they may be reckoned as part of the Chymseyan tribe”.

Kitsumkalum has always been an active participant within the larger Tsimshian Nation. The following are examples of Kitsumkalum participating as an integral part of the Tsimshian Nation:

- The 1909 Letter of Claim[26]

In 1909, the Tsimshian chiefs and Principle Men sent a letter to the government of British Columbia to assert our claims. The collective complaint involved the land question: “… the Government of the Province of British Columbia have disposed of timber on our Hunting grounds from the Canyon on the Skeena River, to Kiteaks [sic] on the Naas River. This land is gone from us to a great extent, the timber has been disposed of by the government, our game is getting scarce our hunting grounds have been taken away” …

It was signed “On behalf of the Tsimpsean People”. This letter is relevant in that it clearly describes the territory of the Tsimshian as being “from the Canyon on the Skeena River, to Kiteaks [sic]on the Naas River.” The “Canyon” is a reference to Kitselas Canyon, which is above the Kitsumkalum territories. According to this letter of claim from the Tsimshian chiefs and Principle Men, Kitsumkalum is one of the Tsimshian peoples, therefore sharing fully in the heritage that exists throughout Tsimshian territory.

- The Council of the Tsimshian Nation

In more recent times, our role within the Tsimshian Nation has been profound. Kitsumkalum was a member in good standing of the Council of the Tsimshian Nation and its successor, the Tsimshian Tribal Council. In fact, these two organizations received important leadership from our members.

The Council of the Tsimshian Nation (CTN) formed in 1980 (approximately) to include all the Tsimshian communities of the Skeena, from Kitselas Canyon to the coast, and Kitkatla, Hartley Bay and Klemtu. Kitsumkalum was an important member of the CTN. The CTN officially selected the name to be an accurate categorization of all these communities.

- The 1982 Statement of the Allied Tsimshian Tribes

In 1982, the hereditary chiefs of nine tribes of Lax Kw’alaams and Metlakatla submitted to the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development a statement specifying their claim for their “aboriginal use and occupation of certain lands and adjacent waters”.[27] The nine tribes referred to by the signatures on this statement are the nine groups in Port Simpson as represented by the Allied Tsimshian Tribes. The statement identified specific territories for each tribe and also territories held in common by all the tribes. Significantly, Kaien Island is identified as a common territory, as distinct from a territory exclusive to one tribe/galts’ap. The 1982 statement intends the expression “all tribes” to refer to the nine represented by the signatures on the document; however, the claim for common territory also aligns with Kitsumkalum’s claim that Kaien Island was a common gathering place for all Tsimshian, including the Kitsumkalum. Furthermore, some of the lineages of those “tribes” live at Kitsumkalum Reserve, are considered to be part of the Kitsumkalum community/galts’ap, and are represented in political matters and social affairs by Kitsumkalum leadership. There is a clear overlap in galts’ap membership and linkage to the common territories of the Tsimshian.

- The Tsimshian Tribal Council

The CTN re-formed into the Tsimshian Tribal Council (TTC) in 1986. Again, the TTC chose a name that would accurately categorize the relationship of the member communities, and Kitsumkalum was an active member.

Kitsumkalum has always been an integral part of the Tsimshian Nation. Dating back to 1846 and the reserve creation process, Kitsumkalum was continuously recorded as Tsimshian. In more recent times, Kitsumkalum has always been an active participant in the larger Tsimshian Nation’s activities and organizations. As a Tsimshian tribe, Kitsumkalum has, and still, enjoys the responsibility for care and use of the common Tsimshian grounds.

Kitsumkalum people are not marginal to Tsimshian society; we are central in many ways. Throughout history, written and oral, we have proven our community to be a key player in Tsimshian society. We were part of the 19th century land disputes, a source of cultural information for the early ethnographers, active in early land claims conferences throughout the province and delegations to government, influential in the founding of the Native Brotherhood, major contributor to the success of Port Essington, and instrumental in the founding of the recent and current Tsimshian political bodies and land claims movement. Kitsumkalum’s leadership has been exceptional within the Tsimshian Nation. Our remarkable history and heritage as Tsimshian is documented in a variety of formats, including books, chapters in books, journal articles, children’s books, reports, and web sites.

- Tsimshian Land Ownership and Use

Before providing some detail on Kitsumkalum’s use and occupation of the Prince Rupert Harbour area and surrounding coast, it is important to recognize that our claims of title and rights are entirely consistent with the traditional land use of the Tsimshian. It is important to understand how the Prince Rupert Harbour and surrounding coast were used by the Tsimshian in accordance with Tsimshian law, or ayaawx, in order to understand Kitsumkalum’s presence at these sites.

Prince Rupert Harbour and the shorelines enclosing it were, at the time of contact and as of 1846, common areas for the Tsimshian to use. The Tsimshian Nation used and occupied these areas to the exclusion of all others. These lands, waters and resources sustained us and were central to what it means to be Tsimshian.

Further, it is essential to recognize that Tsimshian law, ayaawx, provides for the recognition of common areas and allows social groups to claim exclusive use and occupation of specific residential areas along the shore. In her published work, Viola Garfield described the ayaawx that governed how each galts’ap owned its residential site:

Each of the tribes had its traditional stretch of beach upon which it camped. Gradually the members of each house or group of related houses laid claim to particular locations where they had camped for successive years and where they built their plank and brush camp structures.[28]

There is sufficient support for understanding the Prince Rupert Harbour and associated shores as a traditional common area. Garfield’s statements support the proposition that each Tsimshian clan could have exclusive use of beach areas; and, supports Kitsumkalum’s position that it had exclusive use of their settlements. Of special notice are archival maps that document the indigenous property holdings (laxyuup/ territories) under Tsimshian law and correlate the property with specific communities. Not surprisingly, these maps do not identify the west side of Kaien Island with any particular group. In addition, 20th century political organizations and land claims statements have described the area as common for all Tsimshian. Numerous settlements of tribal groups/ galts’ap and house groups/ wuwaap are known to have existed around the Prince Rupert Harbour area throughout Tsimshian history. Oral history and archival documents confirm that Kitsumkalum people traditionally came to the coast to live at their settlements in order to gather their marine resources.

In this way, our ayaawx provides a profound understanding of land rights and land protection. It allows all Tsimshian people to use and occupy our traditional areas, but it vests unique rights and responsibilties with Houses for the care and control of specific sites. These two concepts are not contradictory – rather they work together and are essential to what it means to be Tsimshian.

- Reserve Creation – Royal Commission on Indian Affairs

While our ayaawx enhances the understanding of how Tsimshian used, occupied and owned our lands, the reserve creation process demonstrates a departure from this understanding. Just as the modern myth of “Coast Tsimshian” has created separations amongst Tsimshian and informed incorrect assessments of our claims, the lack of Kitsumkalum Indian Reserves in the Prince Rupert Harbour area has also contributed to a marginalization of Kitsumkalum from these essential areas.

The lack of Kitsumkalum Indian Reserves in the Prince Rupert Harbour and surrounding coast, however, is not an indication that we did not use and occupy those areas, but rather is evidence of the profound disconnect between our ancestors’ understanding of ownership of land, and the understanding implemented in the reserve creation process. Far from Kitsumkalum not being entitled to reserves or not using or occupying these lands so as to justify their allotment, the lack of reserves can be attributed to the fact that Kitsumkalum was ill prepared by the Indian Agent for the process and as such, not aware that the process enabled them to secure more lands. In addition, the gap between the process and Tsimshian law and culture led to a situation where Kitsumkalum resisted reserves in general and specifically did not request reserves on the coast.

Our research has discovered that Kitsumkalum did not want to participate in the reserve creation process. Kitsumkalum Chiefs were very vocal in advising the Royal Commission on Indian Affairs that they did not want reserves; rather, they wished for their land to be held in accordance with traditional Tsimshian law. Kitsumkalum’s experience of being allotted reserve land was not a positive one in our minds. The Chiefs spoke of losing lands as a result of the reserve system, demonstrating that they were not adequately prepared for the process. This is documented in transcripts of the Royal Commission on Indian Affairs, and provides useful insight into the question of why, in the records, Kitsumkalum may not have formally requested any sites in and around the Prince Rupert Harbour and surrounding coast to be set aside as reserve land.

Addressing the Royal Commission in Port Essington, Kitsumkalum Chief Charles Nelson stated that his people wished for the removal of the reserves, and for each family to hold title to their own land:

Every piece of it is sold – the very piece that Judge O’Reilly gave us and told us no one should take it away from us it is all sold.[29]

…

…we are put down as slaves and animals on this reservation business – On this account the reserve is no good to us – why not take the name away – take the reserve name away and let us be a people – let us be free; that is what we want because God gave us this land to live on.[30]

In this same meeting, Mr. Commissioner MacDowall asked Chief Charles Nelson how many people there were in the Kitsumkalum Band, and he responded “No, I am not able to answer that question”. Pressed further, he replied “I could not give you any idea”.[31] The fact that the Chief did not know the answer to this question aligns well with the traditional Tsimshian social organization and land use structure. In Tsimshian law, a chief would only be knowledgeable about his own lineage and House, and its associated territory. This suggests that it was very likely that not all of Kitsumkalum’s interests were represented by the Indian Agent or presented to the Royal Commission on Indian Affairs.

Echoing the dissatisfaction with reserves, and suggesting the community was ill-prepared for the process, Kitsumkalum member Benjamin Bennett said the following to the Chairman of the Commission at Port Essington:

We are placed on the smallest piece of ground at Kitsumkalum – if we were to divide the piece of land on which we are now living, it would not make ten acres to one person. This is the troubles we have on account of the reserve, and that is why we don’t want it. Your Chairman told us to extend the reserve where it needs to be, and we saw it in your “notice” that any plans that are brought up would be attended to. These are the nature of reserves in our mind and we don’t want reserves anymore. I don’t know the meaning of that word “Reserve” – I don’t know that meaning.[32]

This information demonstrates first that Kitsumkalum resisted the reserve process. It is reasonable that having already lost lands, and been placed on small pieces of lands as a result of the reserve process, we were wary to request further sites in fear that we would end up losing more of our territory. Secondly, we were not adequately prepared, as one Chief stated he didn’t know the meaning of the word “Reserve”. Further, the Indian reserve system redefined ownership and shifted the corporate group from the Waap/House as recognized by Tsimshian ayaawx to the Indian Act Bands that exist today. Therefore, Chiefs would not necessarily speak for areas for which they or their family did not have a direct interest in. Between this shift and being ill-prepared, Kitsumkalum did not have the opportunity to request their coastal sites to be set aside as reserve lands.

VII. Kitsumkalum’s Use and Occupation of the Prince Rupert Harbour and Surrounding Coast

Kitsumkalum has, since time immemorial, been an integral part of the Tsimshian Nation. The Tsimshian Nation exclusively occupied the Prince Rupert Harbour and surrounding coast as of 1846. Prince Rupert Harbour and the shorelines enclosing it were common areas for the Tsimshian to use, and the use of resources from these areas has been integral to our culture since first contact with Europeans. As stated above, Tsimshian law, ayaawx, provides for the recognition of common areas and allows social groups to claim exclusive use of specific residential areas along the shore. Being a part of the collective that occupied the coast, Kitsumkalum shares ownership of these common areas, but also asserts exclusive ownership (or title) to certain sites within these common grounds.

Kitsumkalum has always valued our sea food and coastal territory as much as our other Tsimshian relatives. We exercise our aboriginal rights to fish and harvest seafoods as we have done for generations, and continue to utilize our territory for hunting, trapping, gathering, and for engaging in cultural and spiritual activities. We remain an important piece of the Tsimshian Nation and continue to use, gather from, and occupy the Prince Rupert Harbour and surrounding coast.

The following information of our aboriginal use and occupation of the Prince Rupert Harbour and surrounding coast has been collected by: oral history gathered through interviews, archival information consisting of old interview materials and field notes as well as other types of archival sources, archaeological information, published information, and most importantly, the genealogy of the title tribe owners documented in Canada’s records.

Living oral history is available from several elderly community members living today as well as from recently deceased community members recorded as long ago as the 1980s. Oral history records left by elders from other communities, including Lax Kw’alaams and Metlakatla, have also contributed to the understanding of Kitsumkalum’s title and rights related to Casey Point and the Port development area.

What follows is not a complete inventory of the entirety of our archival or traditional use information, and further research is underway. It is provided in this form in order to give sufficient information to strongly ground our title and rights on the coast:

- Exercise of aboriginal rights

Kitsumkalum has, since prior to contact with Europeans and continuously through today, relied upon our territory and rich marine resources of the coast for food, social, ceremonial and economic purposes.

We fished all outside of Prince Rupert harbour… That’s from [?]inside up to Tugwell [Island] all the way to Kinahan [Island], up by Genn Island and down, I forget the name of the pass that’s down there. The Channel on the opposite side of opposite side of Granville Channel

(Wally Miller, Kitsumkalum Elder of the Laxsgiik crest)

Numerous marine species are harvested during the seasonal round within our traditional areas and with techniques that have been passed down from generation to generation. Casey Point served as a home base that connected Kitsumkalum to our coastal sites and sea resources. In a 1999 Traditional Use Study, it was recorded that cedar bark, high bush cranberries, and other berries were harvested in and around Casey Point. From here, Kitsumkalum members would travel to their marine and coastal sites to winter and harvest sea food resources. Kwel’maas has always been an important site for the herring eggs season, starting the beginning of April. Edye Pass is where we harvest abalone, seaweed, yeans, china slipper, scallops, sea cucumbers, sea urchins, clams, cockles, octopus, halibut, cod and crabs. Yeans are sea prunes which we consider a delicacy. We steam them, peel off the cells and spine, and dip them in oolichan grease. Lax Spa Suunt (Arthur Island) serves as a major food resource site for fish eggs beginning in the spring, clams in January and February, as well as, seaweed and halibut. Elders recall staying at the cabins on Lax Spa Suunt for months while they harvested sea food resources. Today, it remains an important camping and resource harvesting site for Kitsumkalum. Mud Bay traditionally served as an important resource site for deer, geese, ducks, sea lions, seals, shrimp, crabs, prawns, halibut, cod, and spring salmon. Today its sea food resources are still harvested, particularly crabs. Halibut is harvested on the coast in the Grenville Channel, Chatham Sound, Edye Pass and the Hecate Straits. Spa Xksuutks (Port Essington), at the mouth of the Ecstall river is an important commercial fishery site. Salmon berries and blueberries are harvested through the Skeena River, Ecstall River and Spa Xksuutks. Today, Spa Xksuutks is sacred ground, as many of our people, elders, and chiefs are buried there.

Other rights we exercise that are integral to our culture in the Prince Rupert Harbour area and surrounding coast include hunting, gathering foods and medicines, and engaging in spiritual activities. Details of the exercise of some of these rights are discussed below with the associated sites.

The coast is a crucial and significant part of Kitsumkalum Tsimshian tradition and culture. Harvesting from our coastal sites has always provided significant subsistence for our community. We continue to exercise our aboriginal rights within and around the Prince Rupert Harbour area and larger coast today, and rely on this subsistence to feed our community and for cultural activities such as feasts and teaching our youth. It also provides us with an economy that is much needed by our people.

- Aboriginal Title to Specific Coastal Sites

The Tsimshian Nation exclusively occupied the Prince Rupert Harbour area and surrounding coast as of 1846. It follows, that Kitsumkalum, as Tsimshian, holds shared exclusive title with all other Tsimshian bands to the Prince Rupert Harbour area and surrounding coast.

As detailed above, Tsimshian law, ayaawx, provides for the recognition of common areas and allows social groups to claim exclusive ownership of specific residential areas along the shore. The Tsimshian enjoy shared exclusive title to the Prince Rupert Harbour area and surrounding coast, meaning each Tsimshian Nation are equally stewards of the land and hold a collective responsibility for care and control of the Harbour area and coast. However, at the same time each Tsimshian Nation holds exclusive title to specific settlement sites within the larger Tsimshian common grounds (the harbour area and coast). The following information provides the details of Kitsumkalum’s use and occupation to some of the sites located in and around the Prince Rupert Harbour area. Kitsumkalum claims shared exclusive title to these areas as Tsimshian, and exclusive title to specific settlement sites at Casey Point, Lelu Island, Kwel’maas, Lax Spa Suunt, Spa Xksuutks, and Dundas Island in accordance with Tsimshian law.

- Casey Point & Barrett Rock

- Casey Point

Casey Point is located on the west coast of Kaien Island. Kaien Island has been well documented as Tsimshian common ground. Kitsumkalum asserts shared exclusive title to Kaien Island, and exclusive title to our settlement at Casey Point in accordance with the ayaawk. Kitsumkalum also asserts exclusive title to a settlement located nearby Casey Point, at Barrett Rock.

Casey Point served as a settlement and resource area, and has great cultural importance to Kitsumkalum. It represented Kitsumkalum’s crucial settlement area for access to the ocean and marine resources. Serving as a base for resource harvesting and a settlement en route to other key locations, Casey Point was strategic for Kitsumkalum’s seasonal economic pattern.

We have compiled a great amount of oral evidence from Kitsumkalum elders speaking to their knowledge and personal reminiscences of Kitsumkalum’s physical occupancy and use of Casey Point. Kitsumkalum has on record over ten elder members who speak to their use and occupation of Casey Point, as well as oral evidence from long deceased elders dating as far back as 1879.

The Kitsumkalum families with a connection to Casey Point include the families of the Gisbutwada Sm’oogyet / Chief Mark Bolton and his wife, the Ganhada matriarch Rebecca Bolton, the family of Ganhada historian Don Roberts Sr., the family of the Laxsgiik Sm’oogyet Louis Starr, and others.

Wally Miller, a Kitsumkalum Elder of the Laxsgiik crest, learned about Kitsumkalum’s coastal heritage from his uncle, Louis Starr, a Laxsgiik Sm’oogyet. Louis told him they used to live at Casey Point and that it belonged to Kitsumkalum. Wally’s memory was that Louis resided at Casey Point when he (Louis) was young[33]. His uncle told him:

Well, when I was a little kid with my uncle on his boat he told me where Casey Point was … we used to – they used to live off there- that’s where they lived. All in that area of Casey Point. That land belongs to us. Of course when I was a young fellow I didn’t pay a lot of attention to what I should of. Otherwise I would have known a lot more history.

Whii Nea ach, of the Laxsgiik Waaps Gitxon living in Kitsumkalum, identified the area as the traditional territory of her Waap (Eagle House).

The late Eddie Feak was a respected Tsimshian historian who was closely related to families in Kitsumkalum. He spoke to the Sm’oogyet ‘Wiidildal, an important leader of Kitsumkalum. This name appears in archival records from the beginning of the 20th century as Alfred Wiidildal. During a 1980 interview, Eddie said Alfred Wiidildal, who was a chief of Kitsumkalum and whose last name is taken from the important Kitsumkalum Gisbutwada title that the man lived on the flats a mile and a half from Prince Rupert, which is approximately where Casey Point lays:

… they [meaning Louis Starr]show me a place. Almost right across Rupert. On that flat, where he had it. Where he had his home. Alfred ‘Wiidildal. … There was a place about a mile and half from that ferry landing, Rupert. On the side that, see that hill coming down, that mountain. Right below it. There’s two foundations, the older village. One village. They claim that, they dig it out, they look at it, and it’s six thousand years old. Yeah, it’s four feet on top of that clam shell that foundation. It’s about two years back there’s a slide on the hillside and the rock tip. You can go up there and see it. There’s Wolf, it’s some kind of a rock, they put it in a, in there, they just discovered it a few years ago. That’s about five, six thousand years ago.

A sketch made by S.F. Tuck in his surveyor field notebook[34] may actually map the location of the cabin and its garden. Tuck surveyed the area in 1886 and recorded sites with active gardening including one just north of the Fairview Container Port development. In some instances, Tuck identified the owners of the gardens that he described but not in this case; however, the location does correspond to the information about Wiidildal’s cabin.

In a 1999 Traditional Use Study, Kitsumkalum Laxsgiik Elder Marge Adams recorded harvesting cedar bark, high bush cranberries, and other berries in the Prince Rupert area, and Ganhada Elder Lloyd Nelson also recorded picking berries near Prince Rupert.

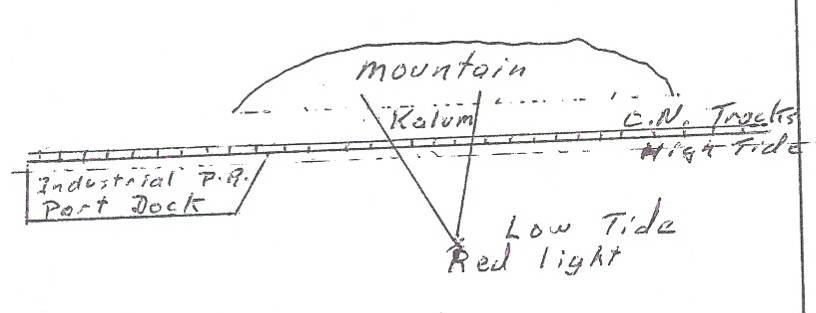

Casey Point has a well delineated traditional location: the boundary of the site was taken at the lowest tide from the “red light marker” that is now located at the point of the gravel bar, along a straight line on each side to the mountain at the back. Describing this boundary, a Kitsumkalum member drew it in relation to the railroad tracks:

Hand sketch of cultural feature at Casey Point site by Chief Don Roberts.

He described in his own words, what his father told him when they were off shore from Casey Point in a fishing boat:

He said stop right here and then he got out and he checked and he was standing on the [deck of the boat pointing to the ]bank, he said you see the way that the shore goes in on… the point, its kinda a round point. But it goes, the shore line kinda goes in an angle, he said you follow that angle in… that was the boundary that was understood by the tribes. There was Kalum then there.

This territorial marker system which identifies the boundaries of Casey Point demonstrates Casey Point as a specific site over which Kitsumkalum retainedexclusive control. This territorial marker system is still known to Kitsumkalum members today. It was recently described on site to government and treaty commission officials when Kitsumkalum took them on a land tour in May of 2013. Also on the tour, middens, trails, water holes and beach formations were identified demonstrating Kitsumkalum’s connection and knowledge of their site at Casey Point.

Casey Point was strategic for Kitsumkalum’s economic pattern, serving as a gathering site, a base for resource harvesting, and a residential site en route to other locations. However, in wintertime, ice and weather conditions made it dangerous to travel to other residences, including those directly associated with the Skeena River such as Spa Xksuutks (Port Essington). This danger was especially true for traditional boats, and is mentioned in oral histories. Indeed, one of the stories about the mythical Robin Woman is about this situation.

The Robin Woman story is a Kitsumkalum adawx (oral history that is a true telling) about the founding of the original town and Robin Woman. Robin Woman was a Kitsumkalum woman who lived at Casey Point and inland at the Kitsumkalum Canyon. Robin Woman is symbolically famous as a herald of spring who opens the winter ice on the Skeena. The story tells how she entered the Skeena in her canoe and sang to break the ice. This story is an important indication of the pre-contact connection Kitsumkalum had to the coast, Casey Point, and its deep connection as part of the Tsimshian Nation. Adawx’s are derived from true events and represent the connection to the land. There are three versions of this story recorded in the archives (Barbeau/Beynon[35], Franz Boas/Henry Tait[36]), demonstrating Kitsumkalum’s connection to Casey Point long before 1846.

A Kitsumkalum Gisbutwada Elder, Mildred Roberts, recalls another story regarding Casey Point and Kitsumkalum’s ancient connection to the area. She recalls a story from when she was young, told by the community Tsimshian historian Eddie Feak:

That’s where our Ts’ak is. It starts [in-audible].This is not just Kalum I don’t think. I think a lot of people knows about Ts’ak. Ts’ak [chuckles] Ts’ak T’’ak is the Chinese Slipper. He keeps asking Giits for dried fish to soak in the creek. And Giits keeps saying [Mildred speaks Sm’álgyax]just wait, wait till there‟s no one outside the creek. So Ts‟ak every morning when he got up he said, since there were no windows he had to open the door [chuckles] and then one morning he did see snow on one side of the tree. So he got excited and asked Giits for the fish. She gave it to him and he ran down the creek and soaked it in the creek, piled some rocks on it so it won’t float away. In the morning he went to look for his fish and it was gone. And he followed, he found the tracks of Mediik in the snow, so he followed it. He found Mediik and he got so mad he hucked that one down called him all kinds of names and one of the names he called him was [Sm’algyax name]tear off his nostril. So Mediik got mad and he [Sm’algyax]that’s snuffing him up. When in, up his nose and Ts’ak went down. And he got one of those little, the bark we call [Sm’algyax]like, he lit it somehow and the ….. [loud back ground noise]turn it off. Then the fat melted in Mediik’s gut and flushed out inside, Ts’ak flushed out like that and and that happened there, by that creek. And Eddie Feak told me, I don’t know what, how he got the [in-audible] but and then he said that happened at Kaien…, by where Kaien Co-op is. And that’s part of you peoples land. He said, your people camped there, and lived there.

One elder provided a very important insight when he described the west side of Kaien Island as a place where people from all the communities gathered and as a common area within which each community had its well known area for its own use. These specific use areas belonged to the particular community that occupied them. In some cases the ‘community’ was a simple family group or Waap/Walp. In other cases it was a ‘tribe’ or galts’ap.

This information that Kitsumkalum had a winter settlement at Casey Point fits the well-known pattern of ‘tribal’ villages around the harbour. The Allied Tsimshian Tribes maps show the lands around Prince Rupert Harbour, including the western portion of Kaien Island to be the Common Ground of the Allied Tribes, without any specific tribal reference. [37] There is also mapped information from Marius Barbeau and William Beynon in the archives that contains sketch maps drawn to accompany textual descriptions documenting certain settlements of individual Tsimshian tribes. However, not all sites were identified with a specific Tsimshian house group. It is worth noting that none of the maps identify the west side of Kaien Island (Casey Point) to any specific Tsimshian tribe. This gap along with our evidence supports our claim that the west side of Kaien Island was generally common ground and a gathering place to all Tsimshian tribes, with specific settlement sites within, including Casey Point, belonging to Kitsumkalum.

Being a common ground, Casey Point also facilitated Kitsumkalum’s participation in the greater Tsimshian society that gathered on Kaien Island and other locations in the area of Prince Rupert Harbour and Metlakatla Pass. Even after the railroad destroyed the Casey Point residential area, members of the community demonstrated how much they valued their participation in Tsimshian society by staying in the area, living at various times in Prince Rupert, Lax Kw’alaams, and Metlakatla.

There are several matrilines/Houses in the Kitsumkalum community that are linked to one of the Metlakatla galts’ap. These galts’aps had traditional residential sites in the Prince Rupert Harbour and the linkages would have extended Kitsumkalum’s residence in the area. The linkages were to the Gitzaxłaał Ganhada through the adoption of Don Roberts Sr. and the family of Addie Turner and Roy Nelson; the Giluts’aaw Ganhada through the family of Rebecca Bolton/ Elizabeth Spalding/ Verna Inkster; the Gispaxlo’ots Laxsgiik through Howard Starr.

The area within and around Casey Point has been studied extensively by archaeologists and all findings have led to the conclusion of Tsimshian presence in that area is an ancient one. The Archaeological Overview Assessment by Millennium Consulting’s Morley Eldridge and Alyssa Parker[38] identified 13 archaeological sites in the Casey Point area: three were previously destroyed, three are culturally modified trees, two are war time bunkers, and five sites have associated lithic materials, shell middens, and canoe runs. Taken together with the evidence of ownership, care and control, this archaeological evidence helps to establish Kitsumkalum at Casey Point since time immemorial.

Casey Point was abandoned as a settlement site in the early part of 20th century due to the construction of the Grand Truck Pacific Railroad (now CNR) along the shore. Construction of the rail bed along the western shore of Kaien Island cut directly through the settlements on the beach front which destroyed heritage sites. This construction was a massive infringement of Kitsumkalum’s aboriginal title and rights to Casey Point and radically changed the relationship of the people to the resource areas. Despite this, Casey Point remains of great cultural significance to Kitsumkalum today.

- Barrett Rock

Kitsumkalum Gisbutwada Elder Bill Bolton remembered his grandmother Rebecca Bolton pointing out the location of a residence at Barrett Rock. In his words:

[the camp was at]Barrett Rock, where the army had their big guns during the war… next to Ridley Island… It was a pretty big camp so it’s probably all along there. That’s where all the Kalum used to stop off and camp there. On the…, either on their way out or where ever they go they used to go. Dundas, Eddy Pass, Arthur Island – in there. Get sea food and that… It’s a big spot. By the sounds of it, there was a lot of people there.

Another Kitsumkalum member, Stewart Bolton (Gisbutwada), remembered his father speaking to Kitsumkalum’s residential site at Barrett Rock:

Well he did say that there was [a camp]beside Barrett Rock. There was something there but he’s never really pointed that out. You know, he’s talked about it. Beside Barrett Rock there was a location there where Kalum there spend a lot more time there. [Like a campsite]… he would fish outside of town or something like that.

Barrett Rock represented an important settlement site exclusively owned by Kitsumkalum. As noted above, Casey Point served as a base for resource harvesting, and a settlement site en route to other key locations including: Spa Xksuutks (Port Essington), Kwel’maas (Island Point), and Lax Spa Suunt (Arthur Island). These locations are discussed below.

- Lelu Island

Allied Tsimshian Tribes maps show Lelu Island as part of the Common Ground of the Allied Tribes, without any specific tribal reference. As a Tsimshian tribe, Kitsumkalum asserts shared exclusive title of Lelu Island with exclusive title to our settlement on the northeast (or mainland) side of the island. Our oral histories speak to our exclusive ownership of our settlement and the evidence shows that we have been active in the area harvesting resources prior to contact with Europeans.

Kitsumkalum members know of their settlement on Lelu Island from their fathers, who were Ganhada leaders. In support of this, Bill Bolton (Gisbutwada Elder) reported that Charles Alexcee, an old man, once told him when Kitsumkalum was having difficulties with the winter to move to their village between Lelu Island and mainland. Lelu Island is also associated with Watson Island. An old settlement site on Watson Island had close connections with the Ganhada Kitsumkalum.

A heritage and impact assessment recorded archaeological sites on Ridley and Lelu Islands, including the presence of culturally modified trees as indicators of long term resource use. Some of these sites were found adjacent to and indeed on the edge of Kitsumkalum’s claimed area, indicating the ancient presence of people there. Note, however, that no survey or assessment of Kitsumkalum’s settlement site itself has been completed. Any proposed activity in this area cannot move forward without a full assessment of this area to be conducted by Kitsumkalum.

- Edye Passage

Edye Passage is the marine area located south of Prince Rupert. This passage is bordered to the north by Arthur and Prescott Islands, to the south and southeast by Porcher Island, and to the west and southwest by Henry and William Islands.

People at Kitsumkalum who grew up on the north coast often share anecdotes and stories which demonstrate our deep personal and cultural attachment to different sites along the Skeena River and at its mouth, including outlying islands. Many of the sites that are important to Kitsumkalum are located in and around Edye Passage. This passage was an important travel corridor utilized extensively to connect our people to some of the larger sites at Kwel’maas (Island Point), Lax Spa Suunt (Arthur Island) and even Stephens Island to the north, as well as to numerous other use sites in-between. Edye Passage is a key ocean area for Kitsumkalum, and a heavy use area for herring and herring roe, kelp, sea weed, and clam beds. It is considered both an important transportation route between coastal resource procurement and a resource procurement area unto itself. Kitsumkalum Laxisgiik Elder Wally Miller describes how we would utilize Edye Passage:

…we’d travel all through that pass anywhere at all. Do our fishing and everything from there. We used to halibut fish too. Just like the Port Simpson does on, on Dundas Island. They got a place out there where they do everything and that’s the way we were over here.

Kwel’maas (Island Point), Lax Spa Suunt (Arthur Island), Stephens Island and numerous other specific sites located in and along the Edye Passage area continue to be important social and cultural places for Kitsumkalum.

- Kwel’maas (Island Point)

Porcher Island lies off the mouth of the Skeena River, south of Prince Rupert. On the north coast of Porcher Island, Kitsumkalum had a coastal camp, called Kwel’maas (or Island Point). The area is part of the Tsimshian Nation’s territory, generally under the control of the Galts’ap Gitwilgyoots. Beynon stated that this was another area that was owned by the entire tribe.[39] Kitsumkalum, as Tsimshian, asserts shared exclusive title to this area, with exclusive title to our settlement at Kwel’maas – one of our settlements along our seasonal rounds on the coast.

Gisbutwada Elder Mildred Roberts of Kitsumkalum said the area was called “Kul-mass” which she translated as mass = bark of tree. This matches the archival name Kwel’maes which William Beynon translates as: ‘where bark’: where = wil; bark = maas.

While she was growing up, Mildred spent time at Kwel’maas with her family. She talks about the many other coastal and inland sites where her family lived on their ‘annual round’, procuring and preserving resources from each site to sustain the family throughout the year:

People from here used to go out there to get their seafood and they could live there until they could come back up the river.

In particular, families travelled between Kwel’maas (Island Point) and Lax Spa Suunt (Arthur Island) to access different types of resources. Our elders know Kwel’maas as the location of a “prime herring egg area” and have identified it as spot where there was a “little cove” where “we get crabs”. Kitsumkalum Laxsgiik Elder Wally Miller called Kwel’maas “Essington territory” and stated “that’s where we get all our seaweed and herring eggs and our abalone. Every year we only took what we – just to eat”.

Kitsumkalum kept several homes at Kwel’maas. These were not simply campsites, but were all considered ‘home’ equally. The structures fell into disuse in the mid-20th century and have fallen down. Little evidence of the houses remains but there are enough of the old timbers and planks to show where the houses stood. Gisbutwada Elder Mildred Roberts recalls nine cabins in particular at Kwel’maas, identified in the figure below:

Mildred explains the placement of the cabins, the owners and their connections to Kitsumkalum:

We lived with my grandparents, Sam and Cecilia Lockerby. That’s my mom’s mother. They had a cabin there, a rustic cabin and it had a porch. I remember that and it had a roof over the porch and then that’s where they hung their herring eggs. But then they had [inaudible] with just a roof and low sidings they weren’t closed in and they hang herring eggs in there. But before that and I knew, Billy wasn’t born then, and we lived in the big cabin that belonged to the Wesley’s. There were two cabins together. They were really well built and ah, one belonged to Robert Wesley and one belonged to David Starr and we lived in one and it was on the other side of where the cabins were with the Lockerby’s.

The cabin was over there that belonged to the Innes’s. That’s where Don’s sister, Doreen [nee Roberts], that’s where she lived with her husband James Innes….Edward McLean [writing his name on the map she is drawing]and then next to them was, ah, Gladys Gray [writing the name on the map], that’s Ben Bennett’s daughter.

Ah… An area that was shared, like he’s Gitksan, McLean, this one – he’s from Glen Vowell I think [Edward McLean is the paternal grandfather of Olive Lockerby (nee Wesley) of Kitsumkalum], and Gladys Grey her mother was from Kitselas and her father was Kitsumkalum, Ben Bennett, and then next to them was Robert Reese from Hartley Bay. It seems like all the people that were living there were the ones that lived in Port Essington. See, they lived in Port Essington and, then Cecilia …she’ll be more recognized….Nelson, Lockerby [her married name]…they are Kitsumkalum and then there were two other cabins there. I know one was in that sort of a little hollow. I think that was John Wesley – another house was in a little hollow-like. He’s Kitsumkalum. And then this one was Paul Starr, he’s Kitsumkalum. And then over here was, ah, Doreen and James Innes [drawing on map]This was Robert’s [Doreen Roberts and Husband James Innes]was Kitsumkalum and his mother was living there too, Rebecca [Innes]. And then behind their place someplace was sort of a little spring and a well and that was the only drinking water. There was two real nice little [cabins]. That was, one was Robert Wesley [drawing on map]and we lived in one of them. Um, David Starr [drawing cabin and writing name on map]I don’t know who owns which one.

They’d get halibut [at Island Point]too. There’s some that lives there and, ah, from herring eggs time to seaweed, like Paul Starr and John Wesley and them and these people (pointing at map she made). But once in a while my grandparents would come across to Lax Spa Suunt at seaweed time and that’s when Sam was halibut fishing and he had all his gear there.

The detail of the knowledge of the cabins and the Kitsumkalum families who lived there demonstrates how well known Kwel’maas was and the significance of the settlement to Kitsumkalum. It also demonstrates how interconnected the Tsimshian tribes are in terms of lineages and intermarriages.

Bob Sankey, a Lax Kw’alaams leader, explained that Porcher Island was an area used by all the Tsimshian and was not just for the Gitwilgyoots or Metlakatla:

Our guys don’t know the area anyway. ‘Cause we used to always go out with Kitsumkalum. Port Essington ones…In all the years we lived in Port Edward, ten years and every year they go for abalone. My brother Don would go out with uh, Sam Lockerby and Lloyd and them hey. Darren McLain. We never went out. He won’t, my dad he won’t let him take his boat out there. He says, “No you go out with them. It’s not our place.”

It’s a, the Ganhadas that lived there were uh, I remember one family, Vera Spence. And uh, in all the years that I remember that was like uh, Island Point area there, all around there, right down to Eddy Pass. It’s all shared with Kalum. Spa Xksuutks , that’s how we knew them, yeah.

You know they’re the guys [Kalum] that have to go out there and we just hop on board on their boats. We don’t go on our own boats. And that’s the way we were taught by our parents, you know. (*40:10 inaudible) belongs to that house group and you respect that and you go along with them and all.

Bob Sankey explained that Kitsumkalum (specifically Port Essington people) had rights to Kwel’maas even though the north end of Porcher Island was generally Gitwilgyoots territory. It is Ganhada territory that was common to all Ganhada. It is not the house that owns common territory, but the crest that owns it:

I remember when uh, the Ganhadas of Gitwilgyoots, they had a place out there at uh, Island Point that they shared with uh, Kitsumkalum. And so intermarriages, then you have Gisbutwadas there and Laxsgiiks and Laxgibuus, , eh? And so they all end up there and we’ve always acknowledged that’s, Kitsumkalum always comes down there. And then so our tribal system and the intermarriages, and people acknowledge that. They include them and whatever they do and they share.

Kwel’maas was and still is an important resource harvesting site for Kitsumkalum. As Tsimshian, we have always enjoyed rights to the area, including our exclusive use of our settlement site.

- Lax Spa Suunt (Arthur Island)

Arthur Island is located south of Prince Rupert. It is buffered between the south eastern end of Stephens Island and the north western side of Porcher Island. The narrow Prescott Pass runs between Stephens Island and Arthur Island, with the larger Edye Passage separating Arthur Island from Porcher Island. The Sm’algyax name is often translated as “Place of Summer” but literately the translation is “On the home of summer” (lax = on; spa = home, place of, den of; suunt= summer).

Lax Spa Suunt is another area that is common to all Tsimshian. It was, and still is, an important spring/summer settlement for Kitsumkalum that is rich in sea food resources. We assert shared exclusive title to this area as Tsimshian, with exclusive title to our settlement.

Lax Spa Suunt was a frequently used resource site for Kitsumkalum families residing in Port Essington, specifically for the Boltons and Lockerbys. Spring was the beginning of the season for Lax Spa Suunt and it served as a rich summer camp for sea foods. Kitsumkalum Gisbutwada Elder Sam Lockerby described Arthur Island as “another hour run” from Island Point. He said “there was quite a few people from all over…people were camping there, harvesting – spawned herring eggs. From Arthur Island, Lockerby said, you’d go back to Port Essington.

Bob Sankey, a Lax Kw’alaams leader, remembered Lax Spa Suunt to be Port Essington territory used by Sam Lockerby (Sr.), Jimmy Bolton, and Ed Bolton:

Well we, we went out, we used to call it Port Essington territory. ‘Cause there were the people who always go out from Port Edwards, Lee Wing and his guy hey? From Port Essington. Yeah, yeah my buddies used to go out with him. And there was, that was their spot for, for harvesting hey? … Yeah I remember that Lloyd Nelson used to go out there for abalone. All Kalum people and my buddy used to jump on board with them. He was friends with them hey? Our guys don’t know the area anyway. ‘Cause we used to always go out with Kitsumkalum. Port Essington ones.

Kitsumkalum Gisbutwada Elder Mildred Roberts described their houses on the island and the resources harvested:

On Arthur Island on this end, this side not where our, our camp was. There were two houses there. One was David Star, William star I think, and one was Robert Wesley’s. They stood side by side there identical real well built houses. Real, real houses {chuckling} you know it had a roof and it had big thick planks. I remember that because we used to go over. But it’s all open and they’re high, maybe I was just little but it looked high. It didn’t have floors but it had gravel. And there are two of the same kind in that porch there.

I keep forgetting the, {in-audible} that’s where the peopled lived, getting, drying their herring eggs, they eat herring eggs.

Seaweed and if they moved out there in the wintertime, January, then they would get clams. They would go down, right down the beach from where they…get clams…They lived there for clams and then herring eggs and seaweed and then go back to Port Essington for gillnetting …

Kitsumkalum Ganhada Elder Ben Bolton described the process of harvesting fish eggs from Lax Spa Suunt:

Oh, fish eggs, you would gather it, you’d probably have to move out to camp from Easter time, start paddling over, or get ready for your fish eggs. You’d have to set up your …, even though you lived at the camp last summer you’d still have to do a little work to change the wood that you used to dry the fish on, your fish eggs on. Then, you see, you’re not there strictly [for harvesting]fish eggs, you’re there gathering all these different types of seafood. Depending on the weather, if it’s good weather on the time you’re there, well, you’re lucky. You’re able to spend more days gathering seafood. And if the weather happens to be bum for the whole week, well, you’re just wasting your time.

Kitsumkalum Gisbutwada Elder Sam Lockerby recalled “there was a lot of us from Kalum” and described the resources harvested on Lax Spa Suunt as:

Mm, like seaweed yeah, abalone, and clams, cockles. Lots of deer on that island years ago.

By the 1950s, the Boltons had re-established themselves at Arthur Island. James Bolton had a cabin there with his wife, Selina, his wife’s Father, Rebecca, his brother Ed Bolton and wife, Sister & Wife’s mother’s husband & family. Other cabins were kept by his Wife’s parent’s, stepfather family, and various other individuals. There was Arthur Bolton, and sometimes Stan Brown. In accordance with ayaawx, the Tsimshian common law, all these people would be living there because of a lineage connection to the laxyuup. This principle was recorded for the neighbouring Gitksan:

“Only men who have rights either through their mother or their father are entitled to reside in a village”[40]