Tsimshian

Northwest Coast

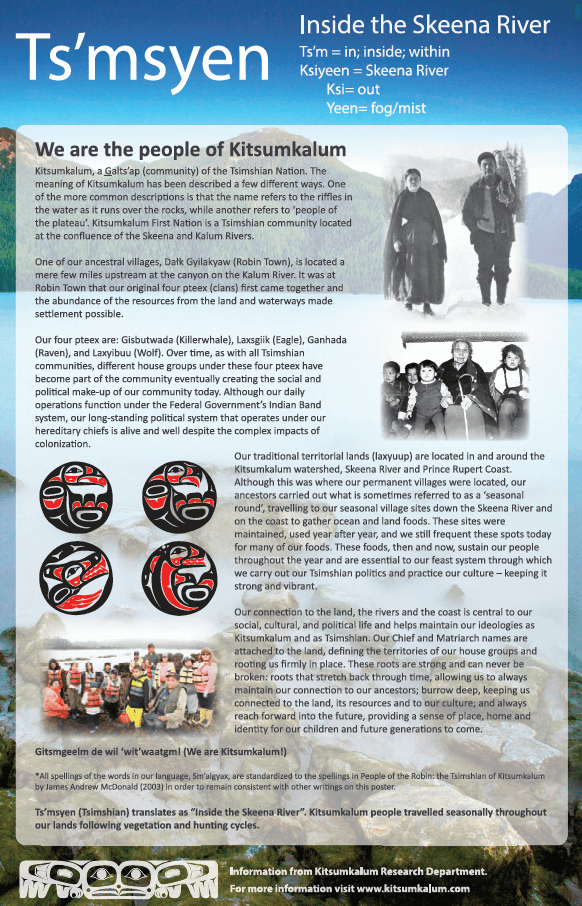

The meaning of Kitsumkalum refers to the riffles in the water as it runs over the rocks, while another description

refers to ‘people of the plateau’.

The contemporary community of Kitsumkalum draws on its ancient Tsimshian culture for values. Our culture is not a dead archive of traditions and customs frozen in the past. We are a strong and proud galts’ap and are an integral part of the Tsimshian Nation with archaeological evidence placing property holdings (laxyuup/territories) in the Kitsumkalum Valley, along the Lakelse and Skeena River, Zymacord, and many special sites surrounding coastal and inland areas of the North West Coast prior to 1846 and as far back as 5,000 years BP.

Kitsumkalum has always been intimately connected to it’s other Tsimshian tribes through marriages, adoptions and the sharing of resources in our common grounds. We come from a traditional and intricate society with complete ayaawx (Tsimshian Law) and rules governing our people, economic rights and relations with other First Nations. We have a sacred trust and responsibility to care for our traditional territory and our connection to the land and coast is part of who we are as Tsimshian. Kitsumkalum has evolved into a modern day society, even after colonization we continue to practice aboriginal rights and title to fish, harvest, gather and engage in cultural and spiritual activities.

Since our Su-sit’ Aatk ceremonies in 1987, we’ve continued making advancements rekindling our house group (waap) traditions of land stewardship, harvesting and economic rights fully in the Tsimshian way of life.

Kitsumkalum is very clearly a Tsimshian Community.

Our Culture Concepts

These related concepts provide a set of ideas basic to Kitsumkalum’s culture and society.

Pteex (crest groups or tribes)

One of our ancestral villages, Dałk Gyilakyaw (Robin Town), is located a mere few miles upstream at the canyon on the Kalum River. It was at Robin Town that our original four pteex (clans) first came together and the abundance of the resources from the land and waterways made settlement possible. Our four pteex are: Gisbutwada (Killerwhale), Laxsgiik (Eagle), Ganhada (Raven), and Laxyibuu (Wolf). Over time, as with all Tsimshian communities, different house groups under these four pteex have become part of the community eventually creating the social and political make-up of our community today. Although our daily operations function under the Federal Government’s Indian Band system, our long-standing political system that operates under our hereditary chiefs is alive and well despite the complex impacts of colonization.

Matrilines (kin groups) & Matrilineal Society

The traditional Tsimshian family is different from the typical English Canadian family. Married couples and their children are an important component of the family structure, and the brothers, sisters, parents, uncles, and aunts of both the husband and wife are important to their family group. However, there is a strong emphasis on the connections each individual has to his or her mother and to the mother’s family

(sisters, mother, mother’s mother, maternal grandmother, and mother’s brother). This group is identified clearly as the larger or extended family of the individual. It consists of a lineage of relatives and, because the lineage is defined in terms of the relationship between mothers and daughters, it is called a matrilineage.

(Matri=mother) The concept of a matrilineage is one of the most important concepts to master in understanding how Tsimshian Society works. An interesting result of this arrangement is that the father belongs to a different matriline than his children. Although father and children are part of the same immediate family, they belong to different matrilines because their mothers are from different matrilines, as was required by laws forbidding people to marry within their matrilines. The arrangement is different than the way the traditional English Canadian family tends to identify with the lineages of both the mother and the father. The difference has profound importance for the community.

Waap (the lineage or House)

The Waap is another key to understanding the operation of traditional Tsimshian society. People point out that the Waap has both a social and a physical presence in Tsimshian society. Socially, a Waap is a family defined by each member’s relationship through the women – the matriline. Physically, the Waap was represented by a number of material objects. Traditionally the most dramatic evidence of the Waap was the house it built, owned, and occupied in the permanent town site of its Galts’ap. Other symbolic objects included ceremonial properties and crests, such as crest (totem) poles, headdresses, dancing blankets, button blankets, or drums. Since the wuwaap do not build the traditional houses any more, today the main symbols are the ceremonial objects. For example, Waaps Lagaax (barred L), once had a house or physical waap at Robin Town and lived there during the winter. This building symbolized the social group that was the family and was decorated with the family crests. A rainbow shown as two parallel lines decorated the front the Lagaax (barred L) house at Robin Town. Today, the wuwaap may no longer have their great wuwaap (houses) for the Waap (family) but they continue to identify themselves physically through their crests. Waaps Xpilaxha is represented today in the crests the Sm’oogyet displays on his blanket, head dress, and talking stick.

Ayaawx (Custom/ Law)

The ayaawx are of great importance. The Tsimshian, like all peoples, have their laws and customs that regulate the behaviour expected from them. These are called the Ayaawx Tsimshian or Tsimshian Laws.

The ayaawx (pronounced “a-YAOW-ach”) consist not only of the laws and rules by which people live with each other, but also how they live with other species and objects in the natural world.

The ayaawx are sanctioned by spiritual powers and by secular authorities, both of whom can reprimand or punish people for the way they behave. These are oral laws, passed on in the feast hall and recorded in the Adawx (oral histories, pronounced as “a’DOW-ach”) and other stories where cases of the law are illustrated.

Galts’ap (the towns and communities)

Kitsumkalum is a Galts’ap (community) of the Tsimshian Nation with administration offices and IR 1 near the City of Terrace in northern British Columbia where the Skeena and Kitsumkalum Rivers meet. In 2015, Kitsumkalum boasted 722 band members, with 256 living on reserve and 466 living off reserve. There are currently 108 homes on Kitsumkalum IR1.

Kitsumkalum Community Infrastructure includes offices for Administration, Economic Development and Resource Management, Hereditary Chiefs and Treaty, a Health Centre, NAGK School, Aboriginal Headstart/Day Care, Fire Hall, Public Works-Maintenance, First Nations Arts & Craft Store (House of Sim-oi-Ghets), Water Treatment Plant, Community Hall, gas station and touchless car wash, RV Park & Boat Launch across from Tempo Gas Bar, Rock Quarry and Industrial Park.

The Galts’ap (Community) and the Waap (House Group)

The Waap plays a subtly different role in Tsimshian society compared to neighbouring societies that are otherwise very similar. For example, among the Gitksan, Houses had more paramount importance to the political economy both in the past and in the present. Despite the many changes brought about during the period of Canadian colonization, the Gitksan Houses have maintained their pre-eminence. Their House structure continues as an important foundation of the land claim they filed in 1985.

While description of the Waap as a matrilineal corporate group applies to both the Tsimshian and Gitksans, the Tsimshians place a much greater emphasis on the Galts’ap. Each Waap belongs to a Galts’ap, imparting to people a number of rights and obligations as members of a common community. The most important rights are those associated with the territories of the Galts’ap and with arrangements for those critical life transitions of the Galts’ap and with arrangements for those critical life transitions such as marriage or death, or for the defence of the properties of the Galts’ap.

Another feature of the Tsimshian system is that a Galts’ap usually has a recognized leader, sometimes called a “village chief” in English. This person is the highest ranking titleholder in the Galts’ap. In cases where the difference in rank between the highest titleholders is minor, there may be no individual who can assume full leadership with proper etiquette. In other cases, the harsh application of the Indian Act displaced the hereditary titleholders in favour of an elected official, leaving the role of a traditional leader severely limited, even meaningless in any practical sense. The position of village chief is often used as a feature distinguishing the Tsimshian from the Nisga’a and Gitksan who do not have village chiefs. However, the comment by Sm’oogyet Xpilaxha, quoted earlier, that the system in Kitsumkalum is similar to that of the Gitksan supports my impression that there was no tradition of a village chief. This, then is a second distinction from the rest of the Tsimshian. This distinction was blurred during the period they lived on their coastal reserve in Port Essington, when their council government, which was organized under the Indian Act, did have a strong tradition of a Head Chief.

The importance of the Galts’ap political organization for the Tsimshian is reflected in the energetic way that the people of Lax Kw’alaams (Port Simpson) have presented and defended their land claims as the nine Allied Tsimshian Tribes, and by the organization of the Tsimshian Tribal Council which recognizes the other Galts’ap as the basic organizational feature of the council.

The Canadian government has recognized the importance of the contemporary Tsimshian Galts’ap in three important ways. First, Indian Reserves were allotted to the various “tribes” with respect to the territories of each Galts’ap. Statements made to the leaders of Kitsumkalum by the Indian Reserve Commission stated that the Government intended the Kitsumkalum to be able to continue to use their properties for hunting and gathering activities, but that the reserves were to protect fishing sites. Second, the government recognized the rights of the Galts’ap by granting authority over certain resources to the representatives of the Indian Bands (Galts’ap). An example is the issuing of food fishing licenses on portions of the Skeena River. Third, the government has accepted the organizational structure of the Tsimshian Nation that incorporates each Galts’ap.

Laxyuup (landed property)

Laxyuup refers specifically to our territory – the village sites, hunting, fishing and other harvesting and picking sites that provide life’s necessities.The laxyuup are the landed properties of the Waap. The concept of laxyuup is important to understand as a foundation of Tsimshian society.

Economically, the laxyuup is the source of our resources needed to sustain our people and provide economic opportunities. Socially, the laxyuup is the home of the family, the place where the children learn how to behave, where they are taught through their culture and learn the histories of their ancestors. Spiritually, the laxyuup bear the history of the Waaps and the Galts’ap. It grounds the people connecting them to their past and the future generations.

Although Canadian legal analysis views aboriginal title through both a common law and an indigenous legal lens, Waap territories and responsibilities – and the way those territories and responsibilities are passed down – are based on a fundamentally different way of understanding property rights than we are used to in the common law context.

Sm’oogyet (Male Chief) & Sigidim hanak (Honored Woman)

The Sm’gyigyet (plural of Sm’oogyet) are the chiefs of the Waap and the sub-chiefs who are heads of lineages. The term Sm’oogyet is applied especially to the head of the Waap but it is often extended to include the lineage sub-chiefs, and can be applied to matriarchs. Matriarchs and high status women are generally called by the term Sigidim hanak (singular: Sigidimnak)

This raises an important issue concerning the difficulty of translating ideas from the Tsimshian language into English. Words that are intended to be the same in translation do not always carry the same meaning. In particular, the English term for Tsimshian titleholder is “chief” but the Tsimshian word for titleholder, Sm’oogyet, refers to a different concept than the English notion of chief. In English, for instance, a chief and a Director of the Board or a Prime Minister are all leaders, but they are different in important ways. As you read this book, you should develop a sense of what is meant by the word Sm’oogyet.

Sm’oogyet status implies ownership of the property and wealth of the Waap. Traditionally, the Sm’gyigyet held the ultimate responsibilities for managing the resources and property of the Waap, a task that involved a great deal of consultation in a form of consensual politics. Colonial laws interfere with these functions, but Sm’oogyet is still expected to embody the values of Tsimshian society, to be a role model, to provide leadership and to maintain a high reputation. The name a Sm’oogyet wears embodies these characteristics through time. In some ways, it is useful to think of a Sm’oogyet name as having a life of its own, independent of any one individual and living from time immemorial into the future. When an individual put the name on, he took on the responsibilities of maintaining it and passing it on, in good standing, to the next Sm’oogyet. He became the name.

Lguwaalksik

The blood line provides the strongest guideline for deciding who will be the next Sm’oogyet. When the title is passed down to the next generation, it usually goes to the oldest son of the eldest sister of the incumbent Sm’oogyet. This decribes the passage of titles through the generations, but when a Sm’oogyet dies, the next Sm’oogyet may be the next younger brother of the Sm’oogyet, a person who is usually much more mature and experienced than the younger nephew. The ascension of the next brother provides continuity of experience in governance, but does not weaken the blood line before the title follows through to the nephew.

A kinship chart shows this person is usually the Sm’oogyet’s eldest nephew. The Sm’algyax term for the heir position is Lguwaalksik (plural kabawaalksik).

The Lguwaalksik is an important concept and position. As a concept, the Lguwaalksik is the “next in line,” the person designated for the leadership role who receives training for the responsibilities of that role. An example of the training is learning to speak in public and learning to provide effective leadership through speaking. In this role, the Lguwaalksik receives some of his training by speaking on behalf of the Sm’oogyet, taking on the special role of the Galdm’algyax. As Galdm’algyax, the heir is able to mature and earn respect of the Waap, which helps him move into the role of Sm’oogyet. Being a good Galdm’algyax is not a requirement for becoming a Sm’oogyet, but it is a demonstration of ability.

Alugyet

Another term that may be used is Alugyet (plural: Alugyiget), which also means speaker but emphasizes that the Tsimshian conduct their business in public. The alugyet is a lower position than the Galdm’algyax and is often a back-up speaker to the latter.

Lik’agyigyet

The status just below that of the Sm’oogyet is that of the Lik’agyigyet (singular: Lik’agyet), the many individual councillors and their lineages who make up the middle class and who assist with the governance of the Waap. Lik’agyet status was an important and common status in most Tsimshian and Nisga’a towns but Marius Barbeau recorded the comment of Xpilaxha Sm’oogyet (Charles Nelson) that there were no Lek’axgat in Kitsumkalum.

Wil’naat’al (Lineage)

Often, wuwaap were related to other wuwaap with whom they shared a common ancestor and history. The history of these groups of related wuwaap usually records a time when an ancestral Waap sent some of its people to relocate elsewhere and to develop another branch of the family. A group of wuwaap related in this way can be called a Wil’naat’al. A Wil’naat’al often consisted of families of foreign relatives that had established themselves among other nations. In Kitsumkalum, all the wuwaap are part of larger Wil’naat’al and often include relatives living among the Nisga’a, Gitksan, and Haida as members of those nations.

Unfortunately the translation of the Sm’algyax words for the important concepts of Wil’naat’al and Pteex usually relies on a single English word: clan. This is very confusing. Two conventions will help avoid misunderstanding. First, and most importantly, we give preference to the Sm’algyax words Pteex and Wil’naat’al rather than the confusing English translations. This is important because those words carry the most accurate sense of the Tsimshian concepts. Translating requires us to find the English word that is closest in meaning to the Sm’algyax, and this easily distorts the original concepts.

Second, when we must use English words in translation, we will also choose the words that most closely captures the original meaning from the Sm’algyax. When we have to use an English term for Wil’naat’al, we will use “clan”. The technical meaning of clan is a group of people who share a known ancestor. This is also true of a Wil’naat’al which is a set of wuwaap that are closely related. The technical term for Pteex is “phratry.” Like members of a clan, the members of a phratry behave as if they are all related but, unlike members of a clan, the members of a phratry do not believe they have a common ancestor. These are classic anthropological distinctions between a clan and a phratry, and help to understand the Tsimshian concepts.

Regrettably, the mistaken translations for Pteex and Wil’naat’al are widely used. Even Tsimshian ethnographer William Beynon worried about the possibility of confusion when he acknowledged he tended to “use the word clan . . . for phratry.” He did not explain why he did this. Given the common usage of the inaccurate English terms, it is easier to abandon them in favour of the Sm’algyax terms.

*All spellings of the words in our language, Sm’algyax, are standardized to the spellings in People of the Robin: the Tsimshian of Kitsumkalum by James Andrew McDonald (2003) in order to remain consistent with other writings on this website. Much of the cultural content on this website can be referenced from James Andrew McDonald (2003), People of the Robin: The Tsimshian of Kitsumkalum book, Kitsumkalum Social History Research Projects and Kitsumkalum elders.

Galdm’algyax

A Sm’oogyet traditionally has a speaker, who is called the Galdm’algyax, or “voice box” (speaker), the person who speaks on behalf of the Sm’oogyet. This position relates to the Tsimshian idea that the words of a Sm’oogyet are powerful. The Galdm’algyax speaks on behalf of the Sm’oogyet and provides a buffer between the Sm’oogyet and the people, a buffer that speaks more softly than can the Sm’oogyet so as to provide more room for negotiation and discussions, a buffer that does not have the power of the Sm’oogyet’s words so as to reduce impact those words can have on an audience.

Frequently, the next in line for Sm’oogyet position, the Lguwaalksik or heir, is trained as the Galdm’algyax. Thus, the two functions are often, but not necessarily, combined in one person.

Lguwaalksik

The blood line provides the strongest guideline for deciding who will be the next Sm’oogyet. When the title is passed down to the next generation, it usually goes to the oldest son of the eldest sister of the incumbent Sm’oogyet. This decribes the passage of titles through the generations, but when a Sm’oogyet dies, the next Sm’oogyet may be the next younger brother of the Sm’oogyet, a person who is usually much more mature and experienced than the younger nephew. The ascension of the next brother provides continuity of experience in governance, but does not weaken the blood line before the title follows through to the nephew.

A kinship chart shows this person is usually the Sm’oogyet’s eldest nephew. The Sm’algyax term for the heir position is Lguwaalksik (plural kabawaalksik).

The Lguwaalksik is an important concept and position. As a concept, the Lguwaalksik is the “next in line,” the person designated for the leadership role who receives training for the responsibilities of that role. An example of the training is learning to speak in public and learning to provide effective leadership through speaking. In this role, the Lguwaalksik receives some of his training by speaking on behalf of the Sm’oogyet, taking on the special role of the Galdm’algyax. As Galdm’algyax, the heir is able to mature and earn respect of the Waap, which helps him move into the role of Sm’oogyet. Being a good Galdm’algyax is not a requirement for becoming a Sm’oogyet, but it is a demonstration of ability.

Alugyet

Another term that may be used is Alugyet (plural: Alugyiget), which also means speaker but emphasizes that the Tsimshian conduct their business in public. The alugyet is a lower position than the Galdm’algyax and is often a back-up speaker to the latter.

Lik’agyigyet

The status just below that of the Sm’oogyet is that of the Lik’agyigyet (singular: Lik’agyet), the many individual councillors and their lineages who make up the middle class and who assist with the governance of the Waap. Lik’agyet status was an important and common status in most Tsimshian and Nisga’a towns but Marius Barbeau recorded the comment of Xpilaxha Sm’oogyet (Charles Nelson) that there were no Lek’axgat in Kitsumkalum.

Wil’naat’al (Lineage)

Often, wuwaap were related to other wuwaap with whom they shared a common ancestor and history. The history of these groups of related wuwaap usually records a time when an ancestral Waap sent some of its people to relocate elsewhere and to develop another branch of the family. A group of wuwaap related in this way can be called a Wil’naat’al. A Wil’naat’al often consisted of families of foreign relatives that had established themselves among other nations. In Kitsumkalum, all the wuwaap are part of larger Wil’naat’al and often include relatives living among the Nisga’a, Gitksan, and Haida as members of those nations.

Unfortunately the translation of the Sm’algyax words for the important concepts of Wil’naat’al and Pteex usually relies on a single English word: clan. This is very confusing. Two conventions will help avoid misunderstanding. First, and most importantly, we give preference to the Sm’algyax words Pteex and Wil’naat’al rather than the confusing English translations. This is important because those words carry the most accurate sense of the Tsimshian concepts. Translating requires us to find the English word that is closest in meaning to the Sm’algyax, and this easily distorts the original concepts.

Second, when we must use English words in translation, we will also choose the words that most closely captures the original meaning from the Sm’algyax. When we have to use an English term for Wil’naat’al, we will use “clan”. The technical meaning of clan is a group of people who share a known ancestor. This is also true of a Wil’naat’al which is a set of wuwaap that are closely related. The technical term for Pteex is “phratry.” Like members of a clan, the members of a phratry behave as if they are all related but, unlike members of a clan, the members of a phratry do not believe they have a common ancestor. These are classic anthropological distinctions between a clan and a phratry, and help to understand the Tsimshian concepts.

Regrettably, the mistaken translations for Pteex and Wil’naat’al are widely used. Even Tsimshian ethnographer William Beynon worried about the possibility of confusion when he acknowledged he tended to “use the word clan . . . for phratry.” He did not explain why he did this. Given the common usage of the inaccurate English terms, it is easier to abandon them in favour of the Sm’algyax terms.

*All spellings of the words in our language, Sm’algyax, are standardized to the spellings in People of the Robin: the Tsimshian of Kitsumkalum by James Andrew McDonald (2003) in order to remain consistent with other writings on this website. Much of the cultural content on this website can be referenced from James Andrew McDonald (2003), People of the Robin: The Tsimshian of Kitsumkalum book, Kitsumkalum Social History Research Projects and Kitsumkalum elders.